Right now, teachers across the country are assessing students using the Fountas & Pinnell Reading Benchmark Assessment System (F&P). If you are not familiar, it is an assessment system which levels different books from A to Z with A being an early Kindergarten level and Z being upper middle school. The assessment gathers a lot of information because the teacher sits down and listens to the child read, marks their reading accuracy/errors, and then asks questions about the text. Questions vary from literal, directly stated in the text to inferential to beyond the text. Teachers can find out lots of information about a child as a reader from this assessment—their ability to track text, use pictures for cues, decode, to read fluently, and to comprehend, and sometimes more.

The window is quickly closing, and a new one will open: parents wanting to know what their child’s reading level is. I am always reluctant to share the letter that indicates the reading levels with parents. Of course, we share the information when requested, but I still worry that it is just one little sliver of information and can often be misinterpreted.

What are my concerns with sharing F&P with parents?

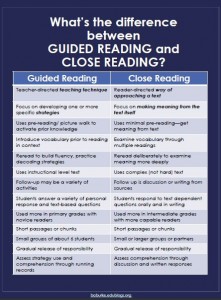

First, this assessment system was created by Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell to benchmark readers in their guided reading instruction. It is essentially a guide to help teachers know when to move students along in the continuum of guided reading books that they use in small group instruction. Each letter-level represents a set of skills that readers have and need to work on. The materials come with very explicit descriptions of what readers should know and be able to do at each level and what strategies and skills are appropriate for them to learn. In short, the benchmarks were intended to be used to guide instruction, not as a method to report to parents.

One Single Measure

Even though this is a thorough and intense measure that may take a teacher 30 or more minutes to complete, it is still only one measure. On one day. With one book (or maybe a few books). because the F&P is administered individually, it can cause students to become nervous. Students can also get tripped up by the topic of the book; if they don’t know anything or don’t have any interest in a particular topic, it can affect their performance. There are very few things in life that rely on a single measure to determine excellence, pass, fail, etc. Even though the Superbowl is one game, previous performance is what drives the teams to get there. We cannot use one performance to be the deciding factor in how we perceive a student’s reading performance.

Reading Growth is a Meandering Path

Reading is complex, and often students do not make steady, incremental progress up the levels in F&P. The benchmarking system indicates a recommended level for students beginning and ending each grade and benchmarks in between. These are approximate levels, and we have found that all students do not go through the levels at the same rate. In early grades, students typically go through the levels/letters more quickly. In first grade, for example, students typically can jump several levels in the school year. By fifth grade, they typically only go up about two letters. While the continuum suggests a typical amount of growth, many students do not follow this normal path. Sometimes students jump several levels in a short time and then slow down.

Some students take a slower path to firmly own the skills in a particular level. Sometimes students struggle with one aspect of reading (for example, decoding multisyllabic words) and that “stalls” them at a particular level. Often students who are early readers “level off” on or near grade level and don’t continue to make the large gains they had in early grades. Sometimes students are growing in skills that are not measured on F&P. Sometimes the particular book or topic of a level is difficult for a student, or sometimes students make gains in other skills that are not monitored by F&P, such as basic comprehension and retelling or their writing skills.

Competitive Reading

I am particularly disturbed by a recent trend we have observed in elementary schools. When a teacher passes out books for a small guided reading group, many immediately flip the book over to see what the letter is on the sticker on the back of the book. Parents quiz their children on what that letter is. We have turned reading into another competitive sport; students want to outdo their competitors and have the highest-level books. We have, in effect, created a Race to Z–a competition among children to get to the highest F&P level possible. This race is causing anxiety and frustration and taking the joy out of reading.

Elephant in the Room: Test Giver Variance

This is the one factor of F&P (or any other individually administered assessment) we don’t like to talk about: different test administrators also can cause some differences in scoring and interpretation. Although we do everything we can to minimize that, the mere fact that each classroom teacher sees things in slightly different ways can impact how they score students’ responses, especially students’ responses to the comprehension portion. So, if one teacher scores particularly “easy” and another is looking for more details and information in responses, it can alter the final “letter.”

The Letter Does Not Say It All

While the letter leveling system takes many factors into account, it is not perfect and definitive system. Relying on a single letter to define a student as a reader is misleading because reading is so much more than that. Just as we as adults read books that are easy for us and hard for us, it is appropriate for students to read books the same way. Literature is rich and wonderful, and teachers are masterful at using terrific books to teach students to comprehend and think. We need to expose students to a wide range of books, and not be limited by the letter on the back.

Inquiring Minds Still Want to Know

So, despite all this, many parents still want to know how their children are doing in reading. Many parents know that schools use F&P, and are going to want to know the level. What should teachers share? First, I am not advocating withholding information requested by parents. I do think it is important to share specific information that will help parents. Instead of just stating the instructional level/letter, describe for parents what that letter or level represents. Here are some questions parents could ask and teachers could answer about students’ reading performance.

Does the student:

- struggle, meet, or exceed grade level standards and skills?

- answer questions in writing or on worksheets at the same level as they answer questions verbally?

- demonstrate any particular strengths?

- prefer fiction or nonfiction or some particular genre or series of books?

- have any skills that will be targeted in guided reading?

It is our job to work with parents as partners in our children’s education. Providing information that parents can use is the key to working together.