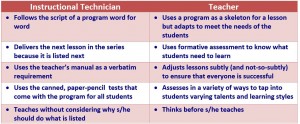

Are you a teacher or an instructional technician?

As our schools are transitioning to Common Core Standards, many teachers are having difficulty. I realize why: most of them have entered the profession in the past ten years; they only have experience teaching by opening a manual and following the prescribed sequence. Common Core State Standards are asking us to do the opposite of this–selecting texts and lessons based on what our students need, matching instruction to our learners. We have bred a generation of teachers who aren’t decision makers first, and lesson plan-followers second.

Many scripted programs are written so that anyone could pick up a manual and start teaching–any substitute or teacher with lackluster skills. Master teachers should be able to rise above this and make instructional decisions–how much time to spend on this lesson, whether to omit or revise that one, whether students are ready to move on, and so on.

CCSS are asking us to move beyond simply being a technician who delivers the lessons, numbly following what some team of authors who never met your students and works in California has written. We are returning to the art of teaching–selecting texts and delivering carefully crafted instruction that has students eating out of the palm of your hand, devouring the text and absorbing the strategies, skills, and ideas you are guiding toward. The art of teaching requires a lot more than simply following the pages in the planner; it requires thoughtful consideration, pondering, planning, assessment, re-tooling, monitoring, and much, much more.

What will we get for all this extra effort? We will get students who are self motivated thinkers, readers, and writers. We will get enthusiasm that builds in our classroom and stimulates us as well. We will get students who are College and Career Ready–the ultimate goal.

When you are designing lessons for your students, these are the questions to ask yourself:

- What do I want my students to learn? Why do I want them to learn this? What are the Common Core State Standards I am addressing?

- How will I know that they have mastered it? What assessment(s) will I use to determine if my students have met this goal or if I need to reteach?

- What will I do with the students who are struggling? There is an old adage that says, “If you do what you have always done, you will get what you have always gotten.” This applies especially to teaching. You can’t just repeat a lesson slower and louder; you have to adjust and try a new approach.

- What will you do with students who have already mastered the skill? This question is not one that we have traditionally considered. The students who came to us knowing the letters and sounds will sit compliantly while you “teach” it to them again. But, we aren’t doing them any favors having them sit and relearn. They should be learning something new.

Let’s agree to attend the funeral of the Instructional Technician, who blindly plods through a manual page by page, day by day. Join me in celebrating the Teacher–instructional lesson designer, assessor, juggler, integrator, mentor, and more.